Signed measure

In mathematics, signed measure is a generalization of the concept of measure by allowing it to have negative values. Some authors may call it a charge,[1] by analogy with electric charge, which is a familiar distribution that takes on positive and negative values.

Contents |

Definition

There are two slightly different concepts of a signed measure, depending on whether or not one allows it to take infinite values. In research papers and advanced books signed measures are usually only allowed to take finite values, while undergraduate textbooks often allow them to take infinite values. To avoid confusion, this article will call these two cases "finite signed measures" and "extended signed measures".

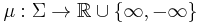

Given a measurable space (X, Σ), that is, a set X with a sigma algebra Σ on it, an extended signed measure is a function

such that  and

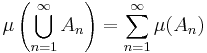

and  is sigma additive, that is, it satisfies the equality

is sigma additive, that is, it satisfies the equality

for any sequence A1, A2, ..., An, ... of disjoint sets in Σ. One consequence is that any extended signed measure can take +∞ as value, or it can take −∞ as value, but both are not available. The expression ∞ − ∞ is undefined (see Extended real number line) and must be avoided.

A finite signed measure is defined in the same way, except that it is only allowed to take real values. That is, it cannot take +∞ or −∞.

Finite signed measures form a vector space, while extended signed measures are not even closed under addition, which makes them rather hard to work with. On the other hand, measures are extended signed measures, but are not in general finite signed measures.

Examples

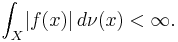

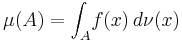

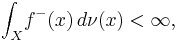

Consider a nonnegative measure ν on the space (X, Σ) and a measurable function f:X→ R such that

Then, a finite signed measure is given by

for all A in Σ.

This signed measure takes only finite values. To allow it to take +∞ as a value, one needs to replace the assumption about f being absolutely integrable with the more relaxed condition

where f−(x) = max(−f(x), 0) is the negative part of f.

Properties

What follows are two results which will imply that an extended signed measure is the difference of two nonnegative measures, and a finite signed measure is the difference of two finite non-negative measures.

The Hahn decomposition theorem states that given a signed measure μ, there exist two measurable sets P and N such that:

- P∪N = X and P∩N = ∅;

- μ(E) ≥ 0 for each E in Σ such that E ⊆ P — in other words, P is a positive set;

- μ(E) ≤ 0 for each E in Σ such that E ⊆ N — that is, N is a negative set.

Moreover, this decomposition is unique up to adding to/subtracting μ-null sets from P and N.

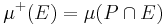

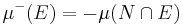

Consider then two nonnegative measures μ+ and μ- defined by

and

for all measurable sets E, that is, E in Σ.

One can check that both μ+ and μ- are nonnegative measures, with one taking only finite values, and are called the positive part and negative part of μ, respectively. One has that μ = μ+ - μ-. The measure |μ| = μ+ + μ- is called the variation of μ, and its maximum possible value, ||μ|| = |μ|(X), is called the total variation of μ.

This consequence of the Hahn decomposition theorem is called the Jordan decomposition. The measures μ+, μ- and |μ| are independent of the choice of P and N in the Hahn decomposition theorem.

The space of signed measures

The sum of two finite signed measures is a finite signed measure, as is the product of a finite signed measure by a real number: they are closed under linear combination. It follows that the set of finite signed measures on a measure space (X, Σ) is a real vector space; this is in contrast to positive measures, which are only closed under conical combination, and thus form a convex cone but not a vector space. Furthermore, the total variation defines a norm in respect to which the space of finite signed measures becomes a Banach space. This space has even more structure, in that it can be shown to be a Dedekind complete Banach lattice and in so doing the Radon–Nikodym theorem can be shown to be a special case of the Freudenthal spectral theorem.

If X is a compact separable space, then the space of finite signed Baire measures is the dual of the real Banach space of all continuous real-valued functions on X, by the Riesz representation theorem.

See also

Notes

- ^ A charge need not be countably additive. A charge is additive: see reference Bhaskara Rao & Bhaskara Rao 1983 for a comprehensive introduction.

References

- Bartle, Robert G. (1966), The Elements of Integration, New York-London-Sydney: John Wiley and Sons, pp. X+129, Zbl 0146.28201

- Bhaskara Rao, K. P. S.; Bhaskara Rao, M. (1983), Theory of Charges: A Study of Finitely Additive Measures, Pure and Applied Mathematics, 109, London: Academic Press, pp. x + 315, ISBN 0-1209-5780-9, Zbl 0516.28001, http://books.google.it/books?id=mTNQvfe54CoC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Cohn, Donald L. (1997) [1980], Measure theory (reprint ed.), Boston–Basel–Stuttgart: Birkhäuser Verlag, pp. IX+373, ISBN 3-7643-3003-1., Zbl 0436.28001, http://books.google.it/books?id=vRxV2FwJvoAC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Measure+theory+Cohn&cd=1#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Diestel, J. E.; Uhl, J. J. Jr. (1977), Vector measures, Mathematical Surveys and Monographs, 15, Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, ISBN 0821815156, Zbl 0369.46039, http://books.google.it/books?id=NCm4E2By8DQC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Dunford, Nelson; Schwartz, Jacob T. (1959), Linear Operators. Part I: General Theory. Part II: Spectral Theory. Self Adjoint Operators in Hilbert Space. Part III: Spectral Operators., Pure and Applied Mathematics, 6, New York and London: Interscience Publishers, pp. XIV+858, ISBN 0-471-60848-3, Zbl 0084.104

- Dunford, Nelson; Schwartz, Jacob T. (1963), Linear Operators. Part I: General Theory. Part II: Spectral Theory. Self Adjoint Operators in Hilbert Space. Part III: Spectral Operators., Pure and Applied Mathematics, 7, New York and London: Interscience Publishers, pp. IX+859-1923, ISBN 0-471-60847-5, Zbl 0128.34803

- Dunford, Nelson; Schwartz, Jacob T. (1971), Linear Operators. Part I: General Theory. Part II: Spectral Theory. Self Adjoint Operators in Hilbert Space. Part III: Spectral Operators., Pure and Applied Mathematics, 8, New York and London: Interscience Publishers, pp. XIX+1925–2592, ISBN 0-471-60846-7, Zbl 0243.47001

- Zaanen, Adriaan C. (1996), Introduction to Operator Theory in Riesz spaces, Springer, ISBN 3-540-61989-5

This article incorporates material from the following PlanetMath articles: Signed measure, Hahn decomposition theorem, and Jordan decomposition. Their content is licensed under the GFDL.